内視鏡汚染はどの程度問題になっているのか?

院内感染や偽感染の発生原因としては、医療機器の中でも、汚染された内視鏡に関連するものが最も大きな割合を占めています1。

米国上院委員会が実施した調査結果では、2012年から2015年の春にかけて、内視鏡を原因として、世界中で少なくとも250の生命を脅かす感染症(スーパーバグ・カルバペネム耐性腸内細菌科細菌を含む)が発生したことが裏付けられています2。

患者の安全性の向上に取り組む米国の非営利団体であるECRIは、内視鏡の汚染と不適切な洗浄を、患者の安全性に関する主要な問題として認識しています。そのため、ECRIが1年ごとに発表するリストである「Top 10 Health Technology Hazards」では、この問題を過去9年間にわたり連続して掲載しています3。

再利用可能な内視鏡におけるバイオフィルムのリスク

通常の洗浄手順では、内視鏡チャネルからバイオフィルムを確実に除去できません21。

そのため、内視鏡再処理において微生物学的監視を通じた感染防止を行うことは、内視鏡内での早期コロニー形成とバイオフィルム形成を検出し、内視鏡処置後の患者における汚染と感染を防ぐために適切です22 。

FDAが感染予防を要求

2015年3月12日、米国食品医薬品局(FDA)は、再利用可能な医療機器の安全性を強化し、再利用による感染因子の拡散の恐れに対処するための新しい行動計画を発表しました4, 5, 6 。

気管支鏡に関するFDAの安全性情報

その後、FDAは医療機器の再処理に関する新しい指針を発表し、内視鏡に関連する感染症の伝染について議論する2日間のセミナーを開催し、MDRレポートの提出がないことについて十二指腸鏡メーカーに警告を行い、 再処理されたフレキシブルな気管支鏡に関連する感染症について安全性情報を発行しました6 。

FDAの介入

2015年3月:

医療機器の再処理に関する新しい指針

2015年5月:

汚染された内視鏡の問題に対応する2日間のセミナー

2015年8月:

内視鏡に関して要求される市販後調査研究

2015年8月:

十二指腸鏡メーカーに対する警告

2015年9月:

気管支鏡に関する安全性情報

2016年11月:

米国の施設で、汚染された気管支鏡のために2人の患者が死亡しました。7

2017年1月:

汚染された気管支鏡に関するMDRのFDAに対する報告数が2016年に183となり、記録上最多となりました。

2018年1月:

汚染された気管支鏡に関するMDRのFDAに対する報告数が2017年に215となり、記録上最多となりました。

2018年3月:

FDAが、汚染リスクを評価するための市販後調査を実施しなかったことについて、十二指腸鏡メーカーに警告を行いました。

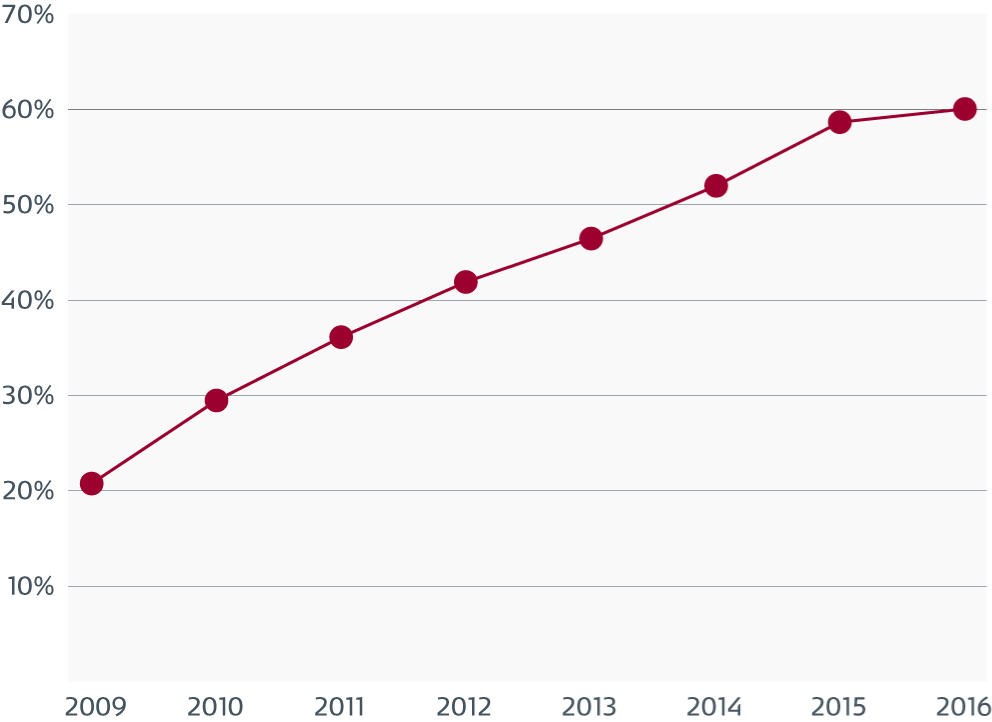

感染リスクの低減を目的とした感染防止基準に対するコンプライアンス違反の継続的な増加

IC.02.02.01 合衆国の病院におけるコンプライアンス違反

合同委員会は、米国の約21,000の医療機関およびプログラムに対して、認定・認証を与えています。

合同委員会基準 IC.02.02.01: 医療設備、医療機器、消耗品に関連する感染リスクを減少させることを、組織に対して要求しています。2009年以降、機器の高レベル消毒(HLD)および滅菌が不適切であるために、IC.02.02.01に対するコンプライアンス違反が継続的に増加しています。

「この時点で、合同委員会は、2013年から2016年にかけて、滅菌が不適切な機器またはHDL機器に直接関連した「差し迫る命への脅威(ITL)」宣言が大幅に増加したことを確認しました。2016年には、全ITLの74%が、滅菌が不適切な機器またはHDL機器に関連するものでした23。」

気管支鏡に関する特別な課題

軟性気管支鏡は、細長い管腔と繊細な素材を持っているため、洗浄や消毒が困難です。それぞれの内視鏡を100%消毒することができるかどうかが問題です。指示された洗浄方法に従っているにもかかわらず、機器の持続的汚染が確認されており、指示された洗浄方法に注意深く従わないと、内視鏡が汚染される可能性があります6, 8。

ルーティン作業として行う洗浄では不十分です。

軟性気管支鏡検査中における二次汚染と感染の真の発生率は、過少報告、不十分な監視、または監視の不存在を理由として、十分に認識されていない可能性があります8, 9。

2013年の軟性気管支鏡検査に関連する感染症について俯瞰したところ、50件の研究が確認されました。公表された50件の研究のうち30件において、患者と気管支鏡で同じ汚染因子が見つかりました。汚染患者の合計569人と、感染患者115人(20.21%)は、汚染された気管支鏡と直接の関連性を有している可能性があります8。

ルーティン作業による洗浄では、内視鏡チャネルからバイオフィルムを効果的に除去できません。13のうち12の内視鏡チャネルで、適切な洗浄手順に従ったにもかかわらず、13のうち13の内視鏡にバイオフィルムが存在していました10。

別の研究によると、45のうち32(71%)の内視鏡に、微生物が増殖していました17。

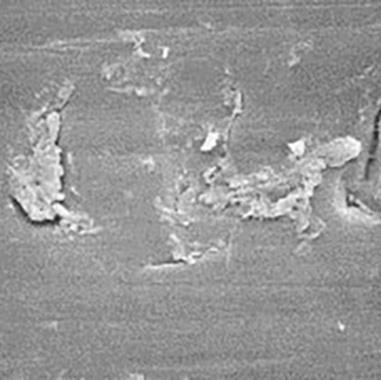

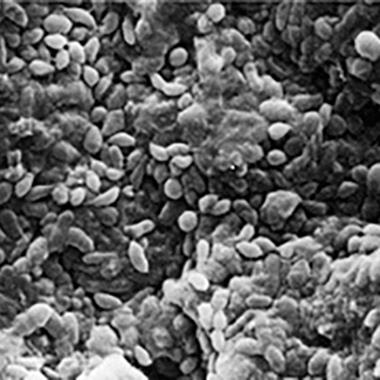

吸引チャネル内の汚れと微生物

表面の欠陥を示す吸引チャネルの電子顕微鏡写真。

生物学的な汚れは、欠陥と関連しており、損傷していない部分にも付着しています。

汚れや、多様な種類の微生物を示す欠陥部分のうち、1つの拡大図。

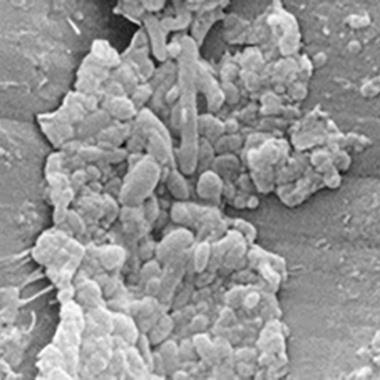

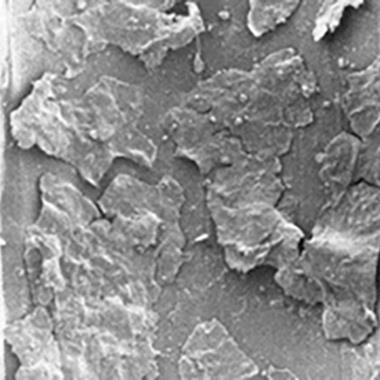

空気/水チャネル内の汚れとフィルム

バイオフィルムを備えた2つの異なる空気/水チャンネルの電子顕微鏡写真。

汚れとバイオフィルムの層が確認できる低倍率の顕微鏡写真。

アモルファスのような菌体外多糖に囲まれ、かつ覆われて、健康に見える細胞からなる多層バイオフィルム。

耐性菌株のリスクが高まっています。

感染症対策に携わる集中治療医、衛生看護師などは、長年にわたって、治療中の患者における汚染と感染のリスクを認識してきました。CREや多剤耐性緑膿菌などの多剤耐性菌(MDRO)の登場は、患者、医師、病院、クリニックが関与するリスクにおいて、新たな問題を生み出しています。

再利用可能な気管支鏡を原因とする薬剤耐性菌の発生が報告されています18,19,20。

気管支鏡が、患者間において、どのように交叉感染の固有リスクをもたらすかについて説明したビデオをご覧ください。

交叉感染の経済的影響

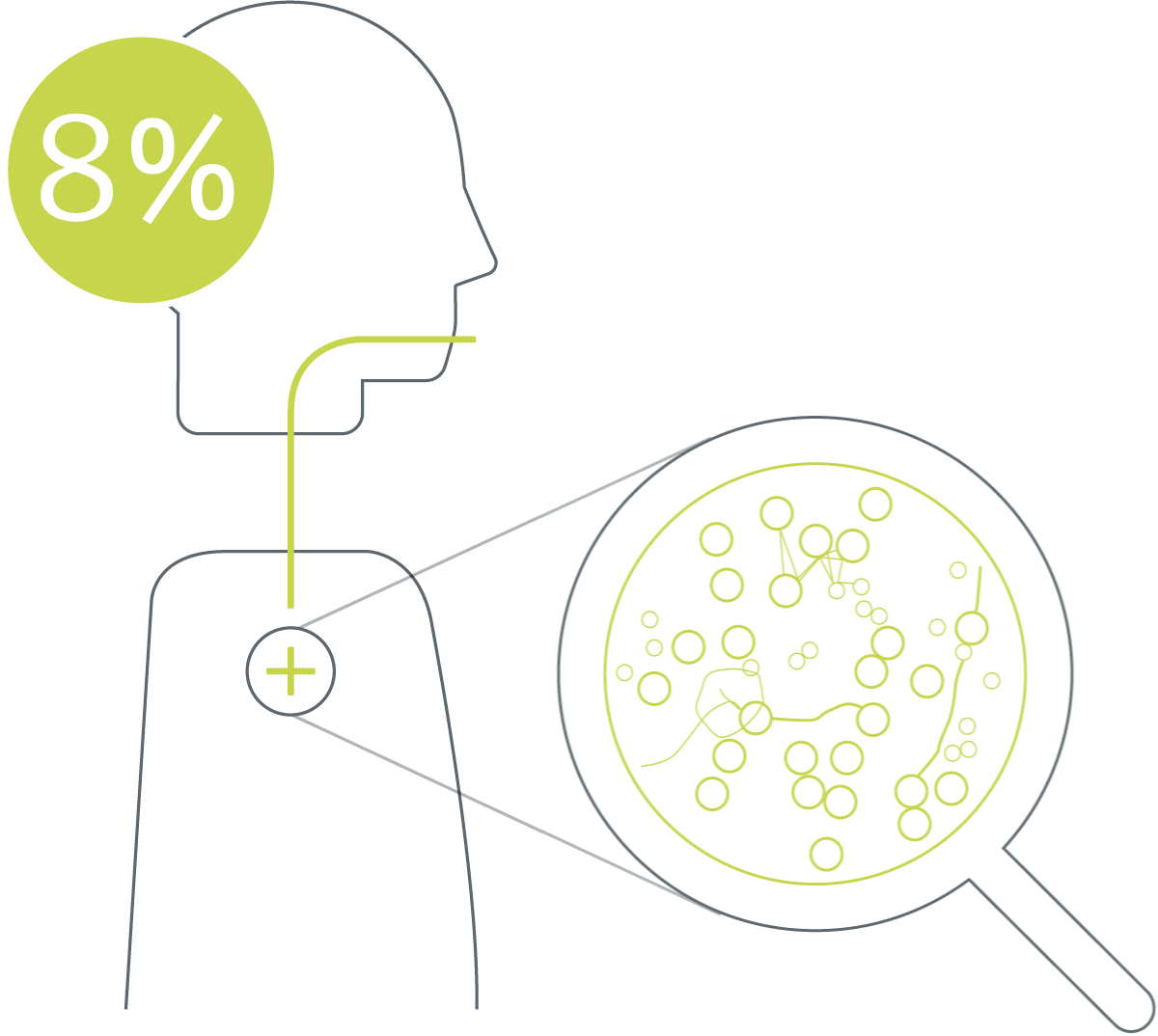

体系的な文献検索の結果を定量化すると、気管支鏡の全体的な汚染率が8.7%であることが明らかになりました。*この分析は、8か国で実施された13件の研究から得られた1664個のサンプルを対象としています25-37。

気管支鏡で汚染された患者の大部分は肺炎を患っているため8,13 、人工呼吸器関連肺炎に関連するコスト(25.149ドル)は、費用計算において、臨床的影響として用いられます。交叉感染のリスク8%と、感染リスク20.21%を組み合わせることで、二次汚染に関連するコストを計算できます。

0.08 x 0.2021 x 25.149 = $407*

*用いた情報源に従い、汚染と感染のリスクに、VAPのコストを加えたもの。

二次汚染のリスク8%25-37 × 感染リスク(Kovaleva et al.8に基づく計算) × 人工呼吸器関連肺炎のコスト($25.149)38。

最近のシュードモナス集団感染では、6人の罹患患者の診断、治療、入院に直接関連する医療費は、患者1人あたり243.000ドルまたは40.500ドルであると推計されました14。

無菌性の保証。すぐに使用可能。

集団感染を原因として、医師は気管支鏡検査の安全性に疑問を投げかけています。気管支鏡を含む内視鏡は、院内感染の発生との関連性が最も高い医療機器です。15, 16

ICUでのベッドサイド気管支鏡検査中、多剤耐性菌による二次感染のリスクは、滅菌済みのシングルユース気管支鏡を使用することで大幅に減少させることができます。

AmbuのシングルユースaScope 4 ブロンコは、包装時点からそのまま無菌状態を確保することにより、交叉感染のリスクを最小限に抑え、不適切な自動内視鏡再処理を原因とする残留バイオフィルムを防ぎます。

参照

CDC Guideline 2008. Disinfection and Sterilization in Healthcare Facilities.

US senate report January 13, 2016 Preventable Tragedies: Superbugs and How Ineffective Monitoring of Medical Device Safety Fails Patients

ECRI Institute https://www.ecri.org/Pages/default.aspx

FDA News Release. FDA releases final guidance on reprocessing of reusable medical devices. March 12, 2015.

Reprocessing Medical Devices in Health Care Settings: Validation Methods and Labeling. Guidance for Industry and Food and Drug Administration Staff. FDA. March 17, 2015.

Go to article: Infections Associated with Reprocessed Flexible Bronchoscopes: FDA Safety Communication

Go to: FDA MAUDE database

Kovaleva et al. 2013; Transmission of Infection by Flexible Gastrointestinal Endoscopy and Bronchoscopy. Clinical Microbiology Rev. April 2013 vol. 26 no. 2, p. 231-254

MM. Mughal et al.2004; Reprocessing the Bronchoscope: The Challenges, Seminars in Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine. Vol. 25 no. 4, p. 443-449

Pajkos et al. Is biofilm accumulation on endoscope tubing a contributor to the failure of cleaning and decontamination? Journal of Hospital Infection 2004, 58:224-229.

Terjesen et al. 2017; Early Assessment of the Likely Cost Effectiveness of Single-Use Flexible Video Bronchoscopes

Michelle Alfa Ph.D.; Endoscope Reprocessing Verification Testing, Presentation, Meeting Materials Non-FDA Generated, FDA Committee Meeting, May 14-15, 2015

R. Douglas Scott II, The Direct Medical Costs of Healthcare-Associated Infections in U.S. Hospitals and the Benefits of Prevention, Division of Healthcare Quality Promotion, National Center for Preparedness, Detection, and Control of Infectious Diseases, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, March 2009

Kovaleva et al. Usefulness of Bacteriological Monitoring of Endoscope Reprocessing, Therapeutic Gastrointestinal Endoscopy, Chap. 9, p. 141-162, 2011

Srinivasan et al. An Outbreak of Pseudomonas aeruginosa Infections Associated with Flexible Bronchoscopes. The New England Journal of Medicine, 2003; 348;221-7

CDC release from the Healthcare Infection Control Practices Advisory Committee (HICPAC) January 25, 2017. "Essential Elements of a Reprocessing Program for Flexible Endoscopes – Recommendations of the HICPAC”

Cori L. Ofstead et al 2018; Residual moisture andwaterborne pathogens inside flexible endoscopes: Evidence from a multisite study of endoscope drying effectiveness

T. Waite et al 2016; Pseudo-outbreaks of Stenotrophomonas maltophilia on an intensive care unit in England.

Janine Zweigner et al 2014; A carbapenem-resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae outbreak following bronchoscopy

T Agerton et al 1997; Transmission of a highly drug-resistant strain (strain W1) of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Community outbreak and nosoco- mial transmission via a contaminated bronchoscope.

Ofstead et al 2017: Longitudinal assessment of reprocessing effectiveness for colonoscopes and gastroscopes: Results of visual inspections, biochemical markers, and microbial cultures

Kovaleva and Buss: Usefulness of Bacteriological Monitoring of Endoscope Reprocessing

The Joint Commission: Quick Safety Issue 33 May 2017

Ofstead et al. 2018 “Effectiveness of reprocessing for flexible bronchoscopes and endobronchial ultrasound bronchoscopes” CHEST

M. Guy et al. “Outbreak of pulmonary Pseudomonas aeruginosa and Stenotrophomonas maltophilia infections related to contaminated bronchoscope suction valves” Europe's journal of infectious diseases epidemiology, prevention and control Eurosurveillance, Volume 21, Issue 28, 14 July 2016

C. Ofstead et al 2016 “Practical toolkit for monitoring endoscope reprocessing effectiveness: Identification of viable bacteria on gastroscopes, colonoscopes, and bronchoscopes.”

Cori L. Ofstead et al. 2018 “Residual moisture and waterborne pathogens inside flexible endoscopes: Evidence from a multisite study of endoscope drying effectiveness.”

P. Batailler et al 2015 “Usefulness of Adenosinetriphosphate Bioluminescence Assay (ATPmetry) for Monitoring the Reprocessing of Endoscopes.”

M. Botana-Rial et al 2016 “A Pseudo-Outbreak of Pseudomonas putida and Stenotrophomonas maltophilia in a Bronchoscopy Unit.”

C. DiazGranados et al 2009 “Outbreak of Pseudomonas aeruginosa Infection Associated With Contamination of a Flexible Bronchoscope”

L. Gavaldà et al 2015 “Microbiological monitoring of flexible bronchoscopes after high-level disinfection and flushing channels with alcohol: Results and costs”

T. Guimarães et al 2016 “Pseudooutbreak of rapidly growing mycobacteria due to Mycobacterium abscessus subsp bolletii in a digestive and respiratory endoscopy unit caused by the same clone as that of a countrywide outbreak”

M. Marino et al 2012 “Is Reprocessing After Disuse a Safety Procedure for Bronchoscopy?”

D. Rosengarten et al 2010 “Cluster of Pseudoinfections with Burkholderia cepacia Associated with a Contaminated Washer ‐ Disinfector in a Bronchoscopy Unit”

N. Shimono et al 2008 “An outbreak of Pseudomonas aeruginosa infections following thoracic surgeries occurring via the contamination of bronchoscopes and an automatic endoscope reprocessor.”

S. Vincenti et al 2014 “Non-fermentative gram-negative bacteria in hospital tap water and water used for haemodialysis and bronchoscope flushing: Prevalence and distribution of antibiotic resistant strains”

T.D. Waite et al “Pseudo-outbreaks of Stenotrophomonas maltophilia on an intensive care unit in England.”

R. Douglas 2009 “The Direct Medical costs of Healthcare-Associated Infections in U.S. Hospitals and the Benefits of Prevention”